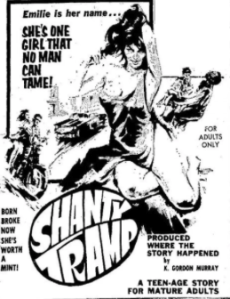

Southern Movie 69: “Shanty Tramp” (1967)

Though it is relatively tame by current standards, 1967’s Shanty Tramp was an “adult movie” in its day. I first came across this film when I was writing about Alabama governor Albert Brewer’s attempts in 1970 to close down theaters that were showing any kind of porn films. After a legal battle typical of Alabama politics, the courts ruled that Brewer had done the right thing the wrong way, so ultimately he lost, and theaters around the state returned to showing these films. In viewing it today, Shanty Tramp is more than a dirty movie. Considering its 1967 release date alongside its unstated location in “Dixie” and its wild plot, the film becomes a commentary on the lives of poor whites in the South and an indictment of the culture’s taboos surrounding interracial sex. Directed by Joseph G. Pietro and starring Eleanor Valli, two Italians whose brief lists of credits are mainly comprised of throwaway potboilers, Shanty Tramp wasn’t made to be a hall-of-famer, but it does provide an example of how outsiders used the Southern paradigm to create storylines.

Shanty Tramp opens with a shot of a young woman in nice knee-length dress walking down a sidewalk at night. A white gospel choir is belting out “When the Saints Go Marching In,” which gives the audience the sense that this story is set in the South. (It’s kind of a poor directorial choice, considering the song’s themes and the film’s plot.) We see this woman from behind, and when the scene pauses for the credits to roll, we are looking at her rear end in the tight dress. When the motion resumes, she saunters past a few men, teasing them silently, smiling at some, but none of them give her more than a look.

Across the street, she sees a tent revival with a stereotypically boisterous white Southern preacher shouting about God and hell and sin and damnation to an audience that sits passively and listens. Our main character, whose name is Emily, goes into the tent but not before a group of bikers roar past in the dark. She ignores them and, in the revival, stays in the back rather than taking a seat. She smiles at the preacher, and we understand that it isn’t his message she is interested in. Also in the back is a young black man named Daniel who is standing with his mother. He keeps eyeing Emily with sideways glances, and his mother tells him to stop looking at the “shanty tramp.” Soon, the preacher gets to his real purpose, which is passing the collection baskets, and he admonishes the small crowd that their faith will be reflected in the amount of cash they put in the baskets.

After the revival, Daniel and his mother leave, but Emily sticks around. She comes on to the preacher, who takes the bait and offers to let her come back to his trailer with him. His sidekick, an older man who does little more during the film than shake his head in dismay, reminds him that there’s still work to do, closing things down. So, the preacher delays his gratification and sends Emily on her way.

Still, Emily is on the hunt for some action! On the sidewalk across the street, she runs into a drunkard, who turns out to be her father. He stumbles around and slurs, seeming to want his daughter to acknowledge him and to behave herself. She berates him and is disgusted by his behavior, and he does little more than say weakly that she shouldn’t treat her father like that. The conversation is brief, she walks away, and he takes a pull from a pint bottle in his coat pocket.

Nearby is a little café-bar that appears to be the local hangout for young people. The lettering across the front of the building declares that it is open from 8:00 AM until 2:00 AM. Inside, Emily finds a young man sitting at the bar by himself, so she walks past the half-dozen young couples who are dancing to the latest tunes from the jukebox. Emily orders a beer and entices the young man to dance with her.

Meanwhile, those bikers from earlier pull into the parking lot. Their leader is a tough guy, and he goes in first with the other four or five following him. These characters remind us of Buzz’s gang in Rebel without a Cause or the bikers in The Wild Angels: a mixture of kooky and badass. Inside, the first couple that the leader encounters is Emily and her newfound beau, and he grabs Emily away from their dancing, while his pals beat the guy up. Everyone else stands by and does nothing. The bikers then take over the place, each grabs a girl for himself, and they spend the rest of the night making out and drinking beers. When it comes time to pay up, they stiff the pitiful guy working there and make their way into the dark to consummate their new relationships. Before she leaves, Emily goes over the pouting proprietor and gets the key to the stock room.

Meanwhile, those bikers from earlier pull into the parking lot. Their leader is a tough guy, and he goes in first with the other four or five following him. These characters remind us of Buzz’s gang in Rebel without a Cause or the bikers in The Wild Angels: a mixture of kooky and badass. Inside, the first couple that the leader encounters is Emily and her newfound beau, and he grabs Emily away from their dancing, while his pals beat the guy up. Everyone else stands by and does nothing. The bikers then take over the place, each grabs a girl for himself, and they spend the rest of the night making out and drinking beers. When it comes time to pay up, they stiff the pitiful guy working there and make their way into the dark to consummate their new relationships. Before she leaves, Emily goes over the pouting proprietor and gets the key to the stock room.

Across town, the young black man Daniel, who we saw with his mother at the revival, is sitting on his front steps, dreaming sadly of Emily. His mother comes outside to tell him that his dinner is cold, but he isn’t hungry. She tells him again to stop thinking of that woman, and he blows her off. His mother then reminds him of the trouble he could get in, even mentioning that his father was lynched when Daniel was too young to remember. Daniel is troubled by this, but we know that he won’t let his infatuation go.

After everyone else has wandered away, following the gang leader’s instructions to go find an alley to get together in, Emily tells her man that she can take him to the back room where there is a mattress. The pair doesn’t know that Daniel is watching from across the street. The biker likes Emily’s idea, but once they get back there, he doesn’t want to pay for her services. She argues with him that their deal involves sex for money, but he isn’t going to pay. She fights him off, but he is too violent for her. He rips her clothes and is going to rape her. Just then, Daniel comes in! He pulls the guy off of Emily and beats him up, knocking him unconscious. Then Emily sets her sights on Daniel, while biker boy lays on the ground nearby. Now, Daniel can be the one who pays and gets some love. But no, Daniel doesn’t want that. He takes off his button-down shirt and gives it to her to cover up, since her dress is torn open. She tells the shirtless man that he can come get his shirt later, in her barn.

Meanwhile, Emily’s father has wandered his drunk self into the tent revival and has been persuaded to change. After listening to the preaching for a bit, he begins to weep and tells the whole crowd that his daughter behaves so badly. She is out there right now, doing those awful things, he tells them. So he stumbles out of the tent to go find her and stop her. The preacher folds his hands and thanks the Lord in Heaven that his good work has been rewarded.

Unfortunately for poor lovestruck Daniel, he goes to the barn later to meet Emily. She is there in his shirt, and he comes in cautiously. Though no sex is shown, we seem them lying together, naked (shown from the waist up) and sleepy, after a brief cut-to. But it isn’t long before Emily’s father shows up. Emily begins to holler to her father for help, saying that she tried to fight him off but Daniel was too strong. Daniel is over to the side, putting his clothes on and wondering, WTF?? When the time came, Emily decides to save her own skin and throw Daniel under the bus. Rather than fight the young black man himself, her father runs to gather a mob.

At this point, we are forty-five minutes into the seventy-minute film. The scandalous nature of the story must have been shocking in the late 1960s. We have a young woman in the South who is anything but a Southern belle, and her character’s actions are counterbalanced against two Southern stereotypes: the unscrupulous itinerant preacher and good-for-nothing, drunken white trash. The biker gang is somewhat out of place in this paradigm, but not too badly. These supporting characters serve to move Emily forward into the act that will be her undoing: interracial sex. Here, Daniel is the good guy, the naive young black man whose lovelorn foolishness causes him to make bad decisions, primarily giving in to temptation and believing in the goodness of a woman who has none.

The rest of Shanty Tramp is fairly predictable, but not altogether. Emily begins to cry after her father leaves and tells Daniel to run into the woods. She wants him to escape, she claims. Back in town, the old drunkard ambles around, finding no one at first, then he returns to the tent, where a crowd is still gathered. He riles them up, and they get organized to find Daniel. Back at the barn, Emily is still lying around topless when her father comes back with the sheriff and a doctor. She refuses to be treated by the doctor, which is a strange sign to the men, especially since she only wants them to “get him” and since she knows where he went. (Why would a rapist intent on escape tell his victim where he would be?)

As the white people in town try to find Daniel, who is slinking through the dark to avoid detection, Emily and her father are back at home. He is putting together the pieces of what he has seen and what he knows. He may be a shiftless drunk but he begins to understand what his daughter was up to. Emily in turn throws a temper tantrum, but her father takes his leather belt and beats her.

Nearby, we see Daniel stumble upon a moonshiner’s shack, as we near the end. Daniel steals a car from the moonshine guys and drives so fast in his getaway attempt that he crashes and dies. We expected things to go like this for Daniel, but here the plot twists dramatically for Emily. Her father, who has just beaten her, decides that since other men get to have Emily, he will too. He yanks off her dress and as he begins to unbutton his own clothes, Emily pulls a knife from the kitchen sink and stabs him repeatedly. Now, she goes on the run. However, the ending comes in a very different way for Emily than for Daniel. Emily comes upon the preacher in his trailer during her escape. The road show is packed up and heading out, and she stows away with him. The car and camper roll away, with the seedy preacher and his new mistress riding comfortably in back. Where Daniel died in a fiery car crash, Emily and her sinful ways will live on.

If you’ve read this far, consider showing some love.

Shanty Tramp traffics in Southern stereotypes to create a noir/porn movie. That aspect of it isn’t as interesting as the way that the film treats the issue of interracial love and sex. Thinking about it in blunt terms, if a young black man were at a tent revival with his mother in the South in the late 1960s, and she caught him looking at a white woman, the mother’s reaction would not be calm and measured. At that time, any black Southern mother, especially one whose husband had been lynched, would be extremely worried about what her son might be thinking or doing. And moreover, the young man would know – just from living in small-town Southern culture – what he was risking, even if he were just caught looking. This might be explained away by the fact that Daniel and his mother are the only black people we see, but I have to remark that it is highly unlikely that you could find a Southern small town with only two black people in it. Nonetheless, this young man is smitten and thinks that the relationship can work out if he pursues it, which is unrealistic. (Hopefully, we all see the parallel with Daniel’s name being the same as the Biblical character in the lion’s den.)

Then we have Emily, a young white woman who would just as soon have casual sex with a black man as a white man. Although love affairs did happen between black men and white women in the Jim Crow South, I doubt if anyone would regard Emily’s feelings as love. She is baldly opportunistic and generally a terrible person. One of the flaws in the storytelling in this film regards that fact. Emily didn’t wake up that morning and decide to start behaving badly. In a small Southern town, everyone would have known her by this age, presumably her late teens or early 20s. Her presence at a tent revival would have been noticed immediately, and her presence in the little café would have been, too. But through the film, no one seems to know her. The only exception is the café proprietor who seems to understand that she uses his storeroom for prostitution. Perhaps the only reason to feel sorry for Emily, from what we know about her in this movie, is that her own father tries to rape her, and she is forced to kill him to resist that happening.

As a document of the South, Shanty Tramp is just wrong enough to be unbelievable. In small Southern towns, where people lived for generations, everyone’s past mattered every day and in every situation. Somehow, though, Emily and her father seem to blend into the crowd in the way that people could in a big city. What I’m saying is: there are Southern elements to this story, but they’re utilized incorrectly. But, if the filmmakers were trying to make a potboiler or a porno, it probably didn’t matter to them. Slapping the “hicksploitation” label on this film is more than fair, since the actress playing Emily spends about ten to fifteen minutes of the seventy without her top on. To be candid, that – not accuracy – was what the audiences were paying for.