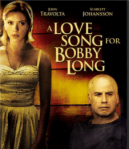

Southern Movie 70: “A Love Song for Bobby Long” (2004)

The Southern Movies series explores images of the South in modern films as well as how those images affect American perspectives on the region.

Based on the novel Off Magazine Street by Ronald Everett Capps, A Love Song for Bobby Long tells the story of a young woman who comes to New Orleans to garner whatever inheritance that her estranged mother may have left her. But what she finds are two degenerate alcoholics who still live in her late mother’s house. Rather than leave the dingy home, the two interlopers use their knowledge of the literary to add flourish and legitimacy to their bad behavior, so this young woman must navigate their strange world in an effort to resolve her mother’s affairs. Through this ordeal, she finds out a little more about humanity and the ways that people cope with their suffering. Directed by Shainee Gabel and starring John Travolta and Scarlet Johansson, the film takes us through a handful of often-sad lives in the seedier parts of New Orleans, and though it does stray from the novel by eliminating some of the more disturbing elements, the humanity in this story still shines through.

A Love Song for Bobby Long opens in a dark barroom where we see man in profile. This is Bobby Long. He is smoking and soon leaves with a bottle in a paper sack. Dressed in a linen suit and a straw hat, and wearing one dress shoe and one flip-flop to accommodate his black big toe, the man limps to the barroom door and opens it to reveal bright sunshine. As a bluesy tune plays, we see him walk through many parts of New Orleans, eventually finishing the bottle and setting it down. Eventually, he arrives at a funeral, sparsely attended, where a voiceover tells us that someone named Lorraine is dead. After the funeral, he is in a raggedy old car with a young man, and they pull up to The Rock Bottom Lounge, where an even more disheveled Bobby struggles to get out of the car. The younger man, who was driving, moves quickly and goes in ahead of him.

Next, our focus shifts to Panama City, Florida, where Lorraine’s daughter Pursy is sitting on the couch in a trailer amid trash, clothes, and a dirt bike. Her scruffy redneck boyfriend Lee comes in, and she asks him whether he has found a job yet. During this conversation, he remarks that that guy Bobby called again. He hadn’t told her that Bobby called the first time— to say that her mother died. Pursy is furious, but Lee wants to ignore Lorraine’s death and go on with life as usual. Pursy storms out with a bag of clothes, ostensibly heading to find out what is going on.

Amid this scene, we break to Bobby and his young counterpart Lawson, who are doing shots in that dark bar. The pretty bartender, who is Lawson’s girlfriend, asks if they’ve finally been kicked out of Lorraine’s house, but the two don’t see it that way at all. Bobby declares that the house is “ours.” Outside the bar, Bobby tries to call Pursy again to say that she missed the funeral, but he gets no answer. The two men and a third friend Junior agree to meet later, and after a short walk, they arrive at small encampment with a trailer, where their friends have gathered. Their friend Cecil is eat a po boy and crying, while they wonder out loud how long Lorraine was sick. It had been six years, and Cecil coldly reminds Bobby how long it had been since he’d visited her. We learn now that Bobby and Lawson have been squatting in the home of a sick woman, and they never took the time to visit.

Soon, Pursy arrives in a cab, and we see her trying to find the house. The small house has a wraparound front porch and is badly in need of paint and repairs. It is an eyesore at the end of the street, with weedy lots beyond it. She bangs on the door, Lawson answers, but at first he doesn’t give her a straight answer about who he is. She comes inside anyway, and the place is sparsely furnished, dirty, and dark. Lawson tells her his name and remarks how Pursy looks like her mother. Then he goes to wake Bobby, who is still in bed, by pouring him a screwdriver. Bobby gulps down the drink and mumbles a few things to Pursy about missing the funeral and “the deal with the house.” According to Bobby, Lorraine left it to all three of them, with one-third ownership each. He has no proof of this, of course, and his face and Lawson’s say that he is lying. The conversation is a tense one, but Bobby informs her that, if she stays, they’ll be roommates. He soon gets out of bed, wearing an Auburn t-shirt, which will become relevant later, and moves past Pursy to go out and buy more cigarettes. After he is gone, Lawson tries to give Pursy a suitcase full of old paperbacks, which he explains were important to her mother, but the young woman doesn’t care. Soon, she walks off down the street, carrying all of her bags.

Later, Bobby and Lawson get drunk in the dark and muse about Lorraine, while Pursy sits in a Greyhound bus station reading The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. She finished the tattered paperback in one sitting, looks at the inscription to Lorraine from Bobby, and returns to the old house. When she arrives, Bobby and Lawson are in a diner eating breakfast, and they return to find Pursy is asleep in a lawn chair in the main room. Bobby pulls up a chair and lays down beside her. When she wakes up, there he is, and he banters at her in a way that mixes intimidation with a cheap come-on. Pursy informs them that she’s staying, and Lawson says that he will clear out of Lorraine’s old room for her. Bobby is miffed at the turn of events, and Lawson reminds him that Pursy will probably leave before she “finds out the truth.”

In Lorraine’s old room, Pursy questions the nature of Lawson’s relationship with her and makes some vague comments about her lifestyle. Lawson is speechless, but he tells her that a stack of boxes in the corner were her mom’s, so . . . they’re hers now. He also replies, to her remark about the books all around, that Bobby was an English professor and that he himself is something of a writer. Pursy is surprised. In a moment, wanting for any food in the house occupied by two alcoholics, Pursy then wanders out of the house and encounters Cecil, who knows her from her childhood. He helped to name her, he explains, after a golden-colored rose. Pursy replies that purselina is actually a weed, not a flower, but Cecil grins and doesn’t accept the slight. Down the street, at the Rock Bottom Lounge, Pursy goes in and asks for some red beans and rice and a beer, and the bartender Georgianna becomes one more person who has something to say to Pursy about her late mother.

When Pursy walks home after an unsuccessful job hunt, she sees the fellas all gathered in the little encampment down the hill. Bobby has an acoustic guitar and is singing a song. She comes down the hill, and Lawson introduces her to everyone. There is one woman there, an older black woman who speaks kindly and introduces herself. Other than her, there are eight or ten men, black and white, drinking beers and cutting up. Bobby wants to make Pursy uncomfortable, so he begins to tell a vulgar story about being a boy and wanting to know what pussy is. His tactic works, and Pursy storms away, leaving the others to grin at Bobby’s antics.

Later, Lawson and Bobby talk in the dark, and Lawson tells Bobby that he doesn’t like lying to Pursy. Bobby replies that the house is a “shithole” that she shouldn’t want. Besides, when Lawson sells the book he is supposedly writing, they will move to Paris and lead grand lives. All the while, Bobby is looking at some photos of a woman and three kids. We don’t yet know who they are.

In the scenes that follow, we see these three lives changing. Cecil takes Pursy to the graveyard to see her mother’s grave, and they talk a little about who she was. Pursy is bitter about being abandoned, and the grandmother who raised her in Lorraine’s absence has died. Back at the house, Pursy begins painting and cleaning up. Across the street in the garden-encampment, Bobby grouches around while Pursy settles into the group dynamic. During these conversations, we learn that Pursy dropped out high school after ninth grade, though we don’t know how old she is. This culminates in a somewhat violent argument between Bobby and Pursy, when the young woman harries the old drunk by refuting his ill-tempered condescension then insulting the mother who did not take care of her. Bobby responds to what he perceives as disrespect by making a lurid suggestion that, because she is not so innocent herself, she might consider paying for her cigarettes by taking on two men at once. Pursy then carries her ire toward him all the way, throwing his drink his face, stomping in his bad toe, and alluding to the wife who threw him out and the kids he doesn’t see. Though we still don’t know his whole story yet, Bobby’s response is to get in the old car and drive to Auburn, Alabama to the campus, where he grimaces silently in the car and rubs his brow in frustration.

The scenes that follow are kind of a hodge-podge. After Bobby is gone, Pursy and Lawson sit on the porch and have a heart-to-heart. She tells him that she might like to become an X-ray technician eventually, but we know that a ninth-grade dropout would have a long way to go to that goal. Next, we see Bobby make a call from a pay phone to a home in the middle of the night. A woman’s voice answers but we do not see him speak before it cuts away. Presumably this is his estranged wife. Back in New Orleans, Lawson is reading a letter from a lawyer, which would indicate that legal proceedings to give the house to Pursy are moving along, and when he storms into the house and enters the bathroom without knocking, we get our gratuitous shot of Pursy’s body as she is getting out of the shower. In the kitchen a moment later, Lawson takes to drinking gin with pickle juice, since they’re out of OJ, then he takes Pursy to the Quarter to hunt for a job. This group of scenes closes out with the two of them talking candidly by the riverside, and we sense the romantic tension between them is growing. That tension increases when later at the bar, Georgianna and Lawson are being cozy, which clearly makes both Lawson and Pursy uncomfortable.

Then Bobby comes home. Lawson and Pursy are on the porch painting the exterior of the house like a couple of newlyweds. Bobby is all smiles, but has the bad news that he sold Lawson’s car because he needed money. Lawson is pissed, but Bobby has news to share. They go inside, and he proudly shows them a doctored transcript that would put Pursy in the twelfth grade. She rails against the idea of going back to school, but the older men believe that she should. Later at the bar, they sweet talk her into accepting their proposal. The next morning, they’re on a street car heading for the private school that Bobby has gotten her into. After a kind of strange scene, in which Bobby talks to a young couple then wants to know whether they’re having sex, they exit the street car hastily and Pursy sees her school. It is a long way from the world she lives in.

Then Bobby comes home. Lawson and Pursy are on the porch painting the exterior of the house like a couple of newlyweds. Bobby is all smiles, but has the bad news that he sold Lawson’s car because he needed money. Lawson is pissed, but Bobby has news to share. They go inside, and he proudly shows them a doctored transcript that would put Pursy in the twelfth grade. She rails against the idea of going back to school, but the older men believe that she should. Later at the bar, they sweet talk her into accepting their proposal. The next morning, they’re on a street car heading for the private school that Bobby has gotten her into. After a kind of strange scene, in which Bobby talks to a young couple then wants to know whether they’re having sex, they exit the street car hastily and Pursy sees her school. It is a long way from the world she lives in.

Next we see them, the trio is at home. Bobby is trying to tutor Pursy like an old timey schoolteacher, and she resists like a modern teenager, whining and complaining. He is an unorthodox teacher, and we see a little of what he might have been like. Once this scene is over, Lawson and Bobby are in the kitchen. Lawson is sweating and dour-looking. He is trying to quit drinking, a promise he made Pursy: she said she would try school if he would cut back. Bobby is no help, though, and he encourages Lawson to pour some vodka in his OJ to get over the hump.

The movie is halfway through now, and the story’s conflicts are in place. Pursy has disrupted the two alcoholics’ routine, but she has ingratiated herself too. Pursy is searching for the truth of her mother, and she and Lawson seemed poised for an unlikely love affair. Bobby and Lawson have half-embraced the teenager girl who wandered into her life, and while Lawson seems poised to help her, Bobby’s behavior mixes efforts to better her and to run her off at the same time. We see change happening in front of us, but we aren’t sure how this will end up.

Of course, Pursy tries to quit school, but the offer of a job at the Rock Bottom Lounge on weekends comes contingent with her being in school. A brief voiceover from Lawson tells us that summer turns into fall, and the whole crew seems happy together in their little community. Winter comes though, and times are hard. They have no heat, and Pursy is trying to help them quit drinking so much. Lawson takes the laundry to wash it, then comes back with a Christmas tree that he stole off the top of a Volvo. While he is gone though, Bobby and Pursy have a heart-to-heart about children and their parents. She stabs at him about the fact that he doesn’t see his kids, why she doesn’t know yet and neither do we. He in return wants to know whether she remembers her mother. She doesn’t, she tells him, so she used to make up fake memories to console herself, but in time, let those go. She doesn’t actually know at this point what she remembers because truth and fabrication have blended in her mind.

Now, the tension comes. When Pursy comes home one evening, she finds Bobby reading Lawson’s book manuscript of him out loud, while Lawson cuts up the pages and makes Christmas tree decorations of the paper strips. Bobby seems pleased, Lawson does not. Then, at the bar, after an upbeat song and a some jubilant dancing, the group sits down at the table together. Everyone is there, and everyone is fine, until Georgianna brings up the idea of Lawson moving in with her. Bobby sours quickly, obviously angered at the idea. He cuts into the couple, telling Georgianna bluntly that Lawson is not in love with her and that he is only enjoying her warm bed. Lawson retorts mildly but Bobby ratchets it up, until a baldly dismayed Lawson finally responds. He tells Bobby that he never asked to be the protege, that he never wanted to write the book about Bobby, and that he is sorry for everything that has happened between them. Lawson and Georgianna leave together, but he stops at her front door, gives a sad look of apology, and returns in the rain to the house.

Back at home, Bobby is pissing blood and is inconsolable at what he believes is Lawson’s departure. Pursy finds him on the bathroom floor weeping and helps him to get up and into the bed. Lawson returns and is attempting to warm himself under a blanket in front of the fire. Pursy comes in, and he opens his arms for her to join him. She asks a few vague questions, probably to avoid the one she really wants to ask: whether he is in love with her. Then, Pursy wants to know what happened between him and Bobby. Lawson sadly explains that Bobby was a popular and charismatic professor at Auburn, and he was Bobby’s teaching assistant. Lawson had a young girlfriend, who was in love with, and through their nights of hanging out and drinking together, Bobby began neglecting his wife and children at home. Then Bobby fell in with Lawson’s girlfriend’s best friend, having an extramarital affair with her. That culminated one night when Bobby’s eight-year-old son had a baseball game. Bobby and Lawson agreed to go late to the game after having a few drinks first. But a young guy came into the bar to challenge Lawson, because he was sleeping with Lawson’s girlfriend and wanted her to leave him. A fight ensued, and Bobby got involved. Meanwhile, the baseball game ended, and the little boy had no ride home, so he tried to walk. On the dark road at night, Bobby’s son was hit by a car and killed, and the reason he was on that road in the first place was that Bobby was in a bar drunk with his young friend and his mistress. Bobby lost everything – his career, his family – so he and Lawson took off to New Orleans in a romantic pipe dream about escaping it all. Now we know why he wears an Auburn t-shirt and hat and why he doesn’t see his kids. And after this confession, Pursy lies down in front of the fire, and Lawson lies down with her. Bobby finds them asleep, but says nothing.

In the morning, it is Christmas. Bobby and Lawson apologize to each other, and Lawson suggests that Bobby go to a doctor. In a quick montage, the friends are all at the house to celebrate, even Georgianna returns with a smile and a bottle of Johnny Walker. By the end of the day, it is raining, and the three smoke on the porch as everyone leaves.

Weeks pass, and it is clearly springtime. Bobby is still pissing blood but refusing medical treatment. Pursy storms in wearing a t-shirt and talking about her exams. After a brief conversation, Bobby agrees begrudgingly to go to the hospital. When Lawson returns, Pursy is in her room, all dolled up in a fancy dress. He is taken aback by how pretty she is, and she relays that she has a date with a boy at her school. Lawson appears about as happy with this has Pursy was about him moving in with Georgianna. But the latent sexual tension remains, and he hopes it goes well

Out on the town, the boy takes Pursy to a jazz club, claiming to love the music. Compared to the older, more seasoned men we we’ve see her around so far, his wide-eyed attempts to impress her seem awkward. In the club, Junior is up on the band stand blowing a horn. He sees Pursy and comes down to speak while he smokes. The conversation, which is moved forward by the bartender who comes over too, implies that Junior might be her father— he played in her band, they bickered sometimes. Junior appears sheepish during this kind of talk, and he soon excuses himself to return to the band stand.

As we wonder about Pursy’s father, Bobby and Lawson have a conversation about what Pursy might do about college. Bobby is mainly worried about himself, but Lawson actually seems to care for Pursy, even acknowledging that she could move on without them. We do find out during this conversation how old Pursy is – she’s eighteen – which means that she has been living an adult life while still a child for some time.

Then Lee shows up. The boyfriend from Florida, who didn’t give her the phone messages, has come to New Orleans to see what’s going on. He has been prompted by a letter from a lawyer, presumably the same letter that Lawson was reading earlier. He sees the potential for moving himself back into her life, but he is the same forceful and angry person we saw in the beginning. He is also the person who enlightens Pursy about the fact that, one year after her mother’s death, she becomes sole owner of the house. What Bobby told her was mildly true, but only in the short-term, not the long-term. She kicks Lee out and re-reads the letter.

When Bobby and Lawson return home, their stuff is on the front porch, and Pursy has locked them out. Bobby bangs on the door, but Lawson sees the letter with a post-it note on it, telling them to get gone. We’ve come to a breaking point in the tension. The relationship has dissolved among the lies and bad behavior, and Pursy, the youngest and least experienced of the three, recognizes that she should act on what is right. Down at the bar, then at Cecil’s place across the street in the garden, the men wonder what Pursy will do with her new knowledge. They know they’re in deep shit when a realtor pulls up and puts a For Sale sign on the front porch. Trying to salvage Pursy’s friendship and their home, they paint the house while she is not at home, but their gesture doesn’t fix the problem. She casually thanks them and goes inside.

While Pursy cleans out the house to leave, Cecil is there to help her, and she encounters the things in the boxes that Lawson pointed out to her near the beginning of the movie. (Apparently, she wanted to know more about her mother, but chose not to look in her mother’s belongings before now.) In one box, she finds a bundle of letters with a note from her mother. She had written these letters but lacked the courage to mail them. There is also sheet music to a song titled “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter,” which points to the idea that Bobby is her father. Cecil half-confirms this suspicion, telling her about Bobby coming to New Orleans, and all of them suspecting that he was her father but not knowing. (While this scenario is heartwarming, it also makes little sense. If Pursy is eighteen years old, then Lorraine got pregnant nineteen years prior to the story we see. That would mean that Bobby and Lawson came to New Orleans nearly twenty years ago, which would mean that Bobby’s “kids” aren’t kids anymore— they’d be in their twenties or nearly thirty. It would also mean, if Lawson was Bobby’s teaching assistant at Auburn, he would have been in his mid-twenties back then . . . so he is about forty-five or fifty now. That makes his fireside cuddles with an eighteen-year-old something else entirely. Yet, this is the story we move into the ending with.)

Pursy finds Bobby and Lawson down by the river, where Bobby is playing and singing. She confronts him, and of course, he did not know that he was her father. Lawson senses the need for privacy and moves away quietly. The two have their father-daughter talk, and Pursy declares that she wants Bobby to replace her fake memories of her mother with real ones. In what may be the movie’s quotable moment, she says, “Life is a book no one takes credit for writing. Everybody knows that books are better than life, that’s why they’re books.” Bobby sees that he has effectively imparted his literary lessons and says yes, he will tell everything. Pursy doesn’t want to sell the house, she was just mad. Everybody wins. (Another problem with this scenario is that it also makes Bobby’s sexual overtures toward Pursy creepy and gross. Even leaving the hospital, he is still saying that’s he’s jealous of Lawson and wants to sleep with her.)

The film ends with Pursy’s graduation, a barbecue with all the friends, and a father-daughter dance on the band stand. We go out with a monologue from Lawson about how Bobby loved the “invisible people,” a reference to Carson McCullers, and that’s what he became. While this monologue goes on, Pursy strides across New Orleans and goes to the graveyard that we saw in the beginning to place a copy of Lawson’s bestselling book on Bobby’s grave, which is right next to Lorraine’s. (One more problem here: Pursy doesn’t lay a copy of the book on his grave for a good long time, if it was out long enough to have gained bestseller status and have a reprint with the “National Bestseller” on the cover. I know that’s publishing nerd kind of knowledge, but several of the film’s storytelling mechanisms here at the end don’t work.)

If you’ve read this far, consider showing some love.

The reviews of A Long Song for Bobby Long, whether from a critic and an ordinary viewer, fluctuate between glowing or harsh. On the website Common Sense Media, their reviewer gave it two stars and wrote, “Not for kids, and not worth it for adults.” Yet the first two parent reviews below that call the movie “fantastic” and “wonderful.” Among Roger Ebert‘s other vague compliments, like the story being mostly believable, the late critic wrote that the “movie tries for tragedy and reaches only pathos.” On the positive side, it couldn’t have been too bad, because Scarlet Johansson was nominated for a Golden Globe for her performance. My assessment of the film is something like the Common Sense Media reviewer’s but with a marked difference: Not for kids, but also not for everybody.

Though the stories are completely dissimilar, this film version of A Love Song for Bobby Long reminds me the film adaptation of Forrest Gump. In both cases, a filmmaker worked with a novel to pull a heartwarming story for mainstream audiences out of a more difficult story. For example, in the novel Forrest Gump, the main character cusses like a sailor and has a destructive college roommate that he likens to a gorilla. Take out the bad language, make Forrest an innocent with a sweet disposition, reduce his college years to football and Jenny, divest him of racism, and you’ve got a nicer story. Some of the main things that the filmmakers changed from the novel Off Magazine Street to have this adaptation are significant. First, Lorraine was not a beautiful singer but was a morbidly obese woman who allowed the two alcoholics to use her body for sexual gratification. On the print page, Lorraine was so overweight that Bobby and Byron (Lawson’s name in the novel) drive her home from the ER in the trunk of the car because she wouldn’t fit in the seats. On screen, Lorraine was said to be lovely, and everyone was enamored with her. Second, in the novel Lorraine died quickly and was not sick for years. Third, in the novel Pursy at first believes that she is waiting on her mother’s disability check, not on the possibility of home ownership. Finally, Pursy’s return to high school with the guidance of Bobby and Byron is more visible. I guess the filmmakers knew that having us see Pursy in high school and having us also see the sexual tension with a middle-aged man would be a problem. Also, Hollywood loves a finding-a-home story. Personally, I’m fairly sure that mainstream audiences would find the nature of the novel’s relationships less palatable. A couple of lost souls finding a family and a home after the death of a beautiful and beloved singer is easier to digest than what Capps offers in the novel.

As a document of the South, A Love Song for Bobby Long is similar in tone and theme to the tale told in A Heart is a Lonely Hunter, which it references several times. This is a story of misfits and outsiders, as Bobby puts it. Every character is damaged and lost, yet they are connected to each other in unconventional ways. Pursy finds redemption by sticking with two drunks who were initially trying to steal her inheritance. She finds an assortment of people who are living destitute lives on the edge of society but who also find beauty in their own ways. Bobby and Lawson love their books, Cecil loves his garden, Junior loves his music. And they find love among each other. Is that particularly Southern? Maybe not. But it could happen.

i have not heard of this movie – looks good

LikeLike