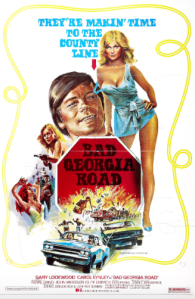

Southern Movie 76: “Bad Georgia Road” (1977)

The Southern Movies series explores images of the South in modern films as well as how those images affect American perspectives on the region.

The 1977 hicksploitation film Bad Georgia Road is one among a slew of these from the 1970s that feature stories involving fast cars and illegal liquor. If you haven’t heard of these films, it’s probably because the majority were eclipsed by the monolithic masterpiece in the genre: Smokey and the Bandit, also from 1977. Despite its name, Bad Georgia Road isn’t set in Georgia at all. The story puts us in Alabama, where young New York City fashionista Molly Golden has come south to claim land that she has inherited from an uncle she never knew. Expecting to find a classic antebellum estate, she instead arrives at a dilapidated homestead— which comes complete with a moonshine operation. That latter part is initially withheld from her, but its continued operation means that the wild and crazy good ol’ boy Leroy Hastings will be coming around in his fast car. Starring Carol Lynley and Gary Lockwood, Bad Georgia Road was directed by John Broderick, who had produced Six-Pack Annie a few years earlier.

The opening scenes of Bad Georgia Road show Leroy Hastings evading two men in a car, as he flies down the backroads in his 1970 Dodge Roadrunner. The pair, who are in plainclothes and not flashing blue lights, are trying to keep up with him. The driver is a buffoonish type in a Civil War infantry cap, while the passenger giving orders and criticizing his performance seems to be a higher-ranking guy. Quickly, Leroy outmaneuvers them by running up ahead, hiding around a curve, then pulling out in front of them. This causes the unsuspecting men to end up in a field as Leroy drives away. As we watch all this, a raucous country tune about moonshining plays.

Soon, we find out about Leroy’s destination. There is a funeral going on in a small graveyard, and a few scroungy-looking people are gathered to pay their respects. The small tombstone reads “Elton Payne, 1897 – 1973.” The hardscrabble bunch amble off after a few words have been said, then Leroy arrives – late – in a pinstriped sport coat with his dirty jeans and t-shirt. Leroy looks like a thirty-year-old former high school football player, stocky with a shaggy non-haircut and an unshaven face. Talking to the elderly man who led the service, Leroy finds out that Elton’s heir “Molly something” is being notified by the local lawyer that she has an inheritance.

Next, we meet Molly in a big city office, where she and a few other women bicker and make catty remarks. She accuses one of them being a closeted lesbian who wants to get in her pants. After a moment, one of the women goes into another room and returns with a set of red padded toy bats, which they will apparently use to beat out their aggression on each other. Before they begin, Molly gets word of a phone call and leaves before the swinging begins. On the other end of the line is a fat country lawyer, who explains briefly that she has been given $100,000 in a bank account and her Uncle Elton’s land in Alabama. She seems elated.

Soon, she and her gay best friend Darryl are riding the two-lane highway in a Mercedes convertible, while Darryl reads out loud from Streetcar Named Desire. They fantasize a bit about what a romantic thing Southern life will be. Then reality hits! Up a long dirt driveway, there it is: old barns, an old house, junk everywhere. As they get out of the car, Arthur Pennyrich – the old hillbilly who officiated the funeral – emerges from the trees and fires his gun at them. Not knowing who they are, he can’t be too careful. But Molly is undeterred. She takes charge of the situation, bossing Pennyrich about his behavior, and retorting that his assistance will not be necessary. Meanwhile, Leroy comes pulling up. His tires throw dirt everywhere, while Molly yells at Pennyrich to stop him. Soon, Leroy comes to halt and gets out of the car. He is guzzling moonshine from a mason jar and throwing his weight around, while a pretty blonde in the car begs to come on and leave.

The aspects of the film’s story are now in place. Bad Georgia Road is one part Thunder Road and one part Green Acres, with the set-up of a romantic comedy. Leroy is a fast-driving wild man, and Molly is a city girl who has come to the country. Our leading man and leading lady are wildly different people, and they dislike each other from the moment they lay eyes on each other.

Back at the house, the portly attorney Depue drives up in his Cadillac to deliver the papers she’ll need to sign. Everything is amicable until she asks when she’ll get the cash. There is no cash, he tells her. She has just signed the papers saying that Uncle Elton’s debts can be paid out of his estate, which means the money was gone before she even came to get it. Molly wants to sell the land then, and Depue informs her with a smug smile that no one in the area will be interested or able to buy it. Molly is stuck in Alabama with no money. She has quit her job, thinking she will have it made. Now, she’s a stranger in a strange land. That evening, she and her pal Darryl discuss the options for how to escape the predicament— sell it to Arthur Pennyrich.

In the light of day, we see Pennyrich in an old blue truck hauling some hay bales across a meadow. In the trees nearby sits the sheriff with his binoculars. He is surveilling the old bootlegger, who picks up on him by the glare on the lens. So Pennyrich pulls out his rifle and shoots the sheriff’s hat off his head, chuckling about he has thwarted the meddling dummy. In the barn, a few moments later, he is loading jugs of moonshine out of the hay bales and into Leroy’s car . . . when Molly walks in. She demands to know what is going, and the men begrudgingly reveal the truth. Molly objects, on the grounds of wanting to avoid prison, but Leroy overrules her by getting in the car to drive off.

He comes back shortly, when Molly is in the yard wearing a green bathing suit and doing something like yoga. He rolls in slowly and, when he gets close to her, tosses a brown paper bag over the roof. It lands beside her. It’s a big stack of cash. Just then, gay best friend comes out to urge her into the plan – they had decided to leave in the morning – but she smiles coyly and declares that she’s starting to like it there. He is dismayed, but can’t do much about it. After he goes back inside, Molly saunters over to the garage where Leroy is cooking eggs. He is dirty and has no pants on. As she tries to speak to him in a friendly manner, he just stares back and eats in a way that is almost animalistic. She is trying to get on his good side, but when he nods his head toward the bed, she takes that as her signal to either go all in or get out.

In the house, Molly does some figuring. Striding out, she beckons Leroy and Pennyrich into the barn, where she makes her offer. She asks how many runs they can make per week, and Pennyrich says five. Molly takes that bit of info and offers the two men 30% of the take, which would come to about $40,000 per year to split between them. She also asks to know the ingredients, which they reveal, and she tells them that buying all that will come out of their end, too. Leroy doesn’t think that’s fair, but Molly retorts, “Without me, you’ve got nothing.” With a sneer, he comes back, “No, without you, we’ve got everything.” However, Molly is undeterred and strides out the barn with confidence. She will get rich off of these two.

The next time Molly sees Leroy, he is pulling to the dirt driveway with a different woman in the car. He once again toss the paper bag over the car to her feet. She doesn’t look amused, and we can tell from her cold expression that she is falling for Leroy. Seeing him with another woman makes her jealous, but it gets much worse when he and this woman go into his little hovel and make a ton of noise. Molly tries to reciprocate, making a pass at Darryl who is still in bed, but not much comes of it.

Out in the yard later, Darryl is lounging on the swing while Molly has set up a place to sunbathe near Leroy’s car. He is tuning it up, and she has a mind to pester him. First, she asks him to adjust her umbrella then to put lotion on her back. She gives these orders with her back turned, so he uses the opportunity to put engine grease in her suntan lotion. Molly comments on the fact that he is always dirty, and he responds that what she really wants is not a man but trained monkey. She calls him a “sexual ghoul,” so Leroy says that, considering how she brought a “queer” down here with her, she must not even know what a man is. They have a quick back and forth about women’s rights and chauvinism, an argument that Leroy sees no point in. Soon, he goes back to his car as she rubs blackish lotion all over her face. Once Molly realizes what has happened, she storms inside silently. Darryl has been watching the whole time, and Leroy gives him a flirty wink to put an end the scene.

Bad Georgia Road is now at the halfway mark. There is nothing unpredictable. Both Leroy and Molly are “types”— he is the rural ruffian, only interested in speed, liquor, and sex, while she is a bossy, greedy feminist from the modern city. Neither one understands the other. Yet, here they are, put together unwittingly.

Bad Georgia Road is now at the halfway mark. There is nothing unpredictable. Both Leroy and Molly are “types”— he is the rural ruffian, only interested in speed, liquor, and sex, while she is a bossy, greedy feminist from the modern city. Neither one understands the other. Yet, here they are, put together unwittingly.

In the scene that follows, we find out about the two men in the opening scene, the ones who were chasing Leroy. The sharper one of the two comes walking through a parking garage and gets into a black limousine. He speaks to an older man, Mr. Larch, who is in the back seat with a pretty young woman. Larch is affable but tells the henchman that something must be done about Leroy Hastings. The young man has been too successful, and the members of their “cooperative” are considering leaving the fold. There are insinuations of organized crime here but nothing overt.

Back in the country, Leroy and Pennyrich are loading up again. Pennyrich tells Leroy to be careful, and knowing what we now know, the admonition is warranted. Leroy is cocksure and brushes off the warning. As he starts to drive away, Molly comes out on the porch to watch him longingly. But then she jumps in the car and demands to go with him. Out on the road, Leroy is flying down two-lane rural byways that are barely paved and not even striped. Molly asks where he is going, and he tells her they’re heading to Birmingham. She wants to know how long it will take, and his reply is to stop talking. Over the CB radio, Leroy talks in code to a man in an office, and that signal is picked up by the two guys from the beginning of the movie. Meanwhile, Molly is complaining about having to go pee, but they have bigger problems. Three carloads of goons are setting Leroy up for the takedown. Leroy evades them by driving through the brush and bushes, yet he creates another problem in his escape: Molly has peed herself.

That evening, they arrive at Simon’s Auto Shop. A grease monkey kid lets them in and banters a bit with Leroy, while Molly changes out of her wet clothes into some coveralls hanging nearby. Leroy tells her to wait around while the car is being worked on, but she disobeys and follows him to a nearby night club. Here, we get an overview of a redneck night out. A country band is playing, and people are dancing. Soon, Leroy calls for a redhead named Lu Anne, who has several men hanging around her. She is all made up and wearing a skimpy pants suit. She and Leroy begin to dance and kiss, until a man comes out of nowhere and snatches Leroy up. They begin to fight, and in doing so, the other man punches Molly in the face. This brings a third guy into the fight, and they all go at it. Until Leroy escapes to the parking lot, with Molly coming out right after him.

After this, it is time for our country boys to have a meeting of the minds. They have to figure out what to do about Larch and his “syndicate.” They have gotten more brazen with the attempt to kill Leroy, so something must be done. The five men who’ve gathered all agree that machine guns are the answer. One claims to have no money, but Leroy quickly corrects him by saying that he has thousands of dollars buried in tin cans all over the place. Pennyrich adds a Southern touch to the conversation but reminding them, “We place our faith in the Lord and our trust in them guns.” Soon, they scatter to set themselves up to go to war.

The next few scenes move quickly among the various aspects of the plot. Out on a dirt road, we see the sheriff with a man who must be his superior or boss. He is being told that they’ve received word about the possible use of machine guns, which means that the goofy little country sheriff will be off the case. He insists that he can handle it, however, by knowing Pennyrich better than anyone. In another area, Molly is skinny-dipping in a pond, and Leroy shows up to request that she rethink his percentage, considering his level of risk. After their conversation, he walks off with her clothes. Back at the house, the sheriff shows up in women’s clothes, claiming from a distance to be a traveling evangelist named Sister Bessie, but Pennyrich sees through the disguise and sets him up to be had. Unfortunately, Pennyrich’s plan to scare the sheriff goes too far, and his car goes off a hillside, crashing into the brush. Pennyrich is scared that he has killed him, but the sheriff secretly scurries into the woods and escapes before the car blows up.

Back at the house, everything is coming to a head. Leroy is drinking on an old seat outdoors when Molly finds him. She made it home from the pond and has put on her silk nightie. The two begin to fuss and fight, which takes them into the house, where Leroy forces himself on her. To her surprise, he stops short of assaulting her and leaves the house laughing. Molly grabs the shotgun and follows him to his little place in the garage, barging in the door to shoot him. Leroy tells her either to admit that she wants him, or to lie to herself and say she doesn’t then shoot him. She answers his dare by pulling the trigger, but he has already taken the shells out of the gun. Half-angry and half-lustful, she storms across the room and jumps on top of him. It is in this awkward way that the two finally get together.

Later, after they’re done, Pennyrich shows up drunk as a skunk. He is having remorses about killing the sheriff, which he didn’t really do, and will no longer be making moonshine. After he leaves the little shack, rambling like a mad man, Leroy tells Molly that they will have yet another new deal. With Arthur gone, she will have to start working at the still with him.

Out at the still, Molly is quickly tired of working. She tries to lay down, but Leroy drags her off the a stack of feed sacks by her feet. As they tussle, she attempts to hit him, and he warns her, “You’re about to eat your teeth.” It keeps on going, so he punches her in the face, knocking her to the ground, and then picks her back up and exerts his authority. From there, he is a tough boss, kicking Molly in the seat of the pants and yanking her by the arm.

The final scenes of Bad Georgia Road resolve the little bit of tension that remains in the story. After being forced by Leroy to drink some of the moonshine, Molly is falling down drunk. But they’ve got a run to make. She insists on going with him. Out on the road, we see one last attempt by the syndicate guys to trap Leroy. And once again he evades them, leaving them in a field just like he did at the beginning. Right before the credits roll, Leroy and Molly are still negotiating their percentages, arguing over how to split the money.

Watching movies like this one reveals why Smokey and the Bandit was more successful than most in this genre. Audiences in the 1970s – and audiences today – can enjoy an outlaw story, a tale about two good ol’ boys eluding the police, generally having a good time doing it, even a story that includes a little love component with a pretty woman added in . . . but audiences are not so fond of men who never bathe, who attempt rape, and who rely on domestic abuse to maintain control. Because of those harsher elements, it’s hard to say what we’re supposed to take away from this story. Molly arrived in Alabama as a citified young woman with a professional career and a gay best friend, then she ends by becoming the girlfriend of a greasy redneck moonshiner who recently punched her in the face. Are we supposed to understand that Leroy showed her the error of her ways or that she likes this new life better? Hopefully not. But there is no moral judgment here, definitely not against Leroy. As for other male characters, they get off scot-free, too. Darryl just abandons Molly without a word, even stealing her car, and the Southern lawyer DePue tricks an unsuspecting woman and cheats her out of her inheritance. But this seems to be where Molly wants to stay. What the hell . . . ?

As a document of the South, Bad Georgia Road combines several elements that are or have become well-known. One is the Simon Suggs figure, that character in the lore of the Old Southwest made famous by Johnson Jones Hooper. Simon Suggs was the early nineteenth century’s backwoods trickster who, in each tale, outsmarts educated and urbane people through a mixture of wily cunning and extreme naiveté. He is the embodiment of a kind of humorous wit that has pervaded Southern culture in works ranging from the novels of Mark Twain to the TV show The Dukes of Hazzard. It is easy to see features of Suggs in both Pennyrich and Leroy. Another element is a generalized Southern locale that gives few or no specifics. There are only a few references to the story being set in Alabama; one is Leroy’s statement that their destination is Birmingham, but when Molly asks how long the trip will take, he doesn’t answer. So how far from Birmingham were they? It’s important to point out here: this movie definitely wasn’t filmed in Alabama. The landscape is obviously California; when they arrive in “Birmingham,” there are palm trees. Just sayin’ . . . Moreover, there’s the title: Bad Georgia Road. There really is an Old Georgia Road in central Alabama, as well as an Atlanta Highway. But not once did anyone in the movie reference such a road that would lead to Georgia. I understand the temptation to put the story in “the South,” but a particular setting matters. South Georgia is not like north Alabama, which is not like the Mississippi Delta, which is not similar to coastal Carolina. I realize that exploitation films are not known for their accuracy, but many Americans do take their conceptions of what the South is from films.

As a last word, other components of this movie are also just plain odd. For example, not one black person appears in this film at all. I realize that it is a racist trope to throw in a token black character or two, usually in a minor role or as extras, but the absence of black characters is notable in a movie that is supposed to be Southern. Second, it was hard to tell whether it was hot where they were. There were scenes when Leroy was in a t-shirt while Pennyrich was in two shirts and an overcoat. And neither man was sweating or shivering. In Alabama, heat and humidity matter. Beyond that, in some parts but not all, the steering wheels of cars are on the right side like they are in Europe, and at about the fifty-minute mark, the sign for Simon’s Auto Shop is clearly backwards. For a movie that centers on cars and driving, it made me wonder what was going on with that. I’ll give them this: the film was a cheaply made drive-in feature, so it is what it is.