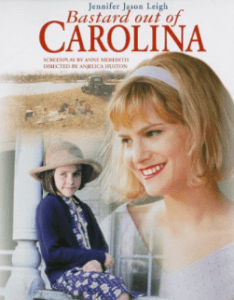

Southern Movie 78: “Bastard Out of Carolina” (1996)

The Southern Movies series explores images of the South in modern films as well as how those images affect American perspectives on the region.

The 1996 made-for-TV adaptation Bastard out of Carolina brings us the story of a girl named Bone, born Ruth Ann Boatwright to a single mother in a rural community and an absent father whose name is never spoken. The film is based on Dorothy Allison’s 1992 novel of the same name, which was a Finalist for the National Book Award. (The story is based heavily on her own life.) The movie, made for the cable channel Showtime, was controversial at the time of its release for its brutally realistic handling of a sexual assault against a child, though it won director Anjelica Huston an Emmy. Jennifer Jason Leigh stars as Bone’s mother Anney, and first Dermot Mulroney then Ron Eldard as her two stepfathers. Playing Bone was actress Jen Malone’s first major role. Bastard out of Carolina offers a harsh look at life in the backwoods regions of the Carolinas in the years after World War II.

The opening scenes of Bastard out of Carolina have us watching four people riding in a black sedan down a rural two-lane road. Three adults are in the front: a man driving, a man in the passenger seat, and a woman in the center. They are drinking and allude to getting to an airport. Soon, they make reference to a fourth passenger, a woman sleeping in the backseat. She is the sister of Earle, the man in the passenger seat. However, momentarily, the driver stops paying attention to the road as he looks through the glove compartment for cigarettes and rear-ends a truck, which throws the sleeping woman in the backseat of the windshield. She is pregnant and hurt badly. At the hospital, the expectant mother Anney (Jennifer Jason Leigh) survives, and Bone is born.

There is a jovial scene at the hospital as Anney recovers, yet the celebratory tone changes when Anney’s sister Ruth (Glenne Headley) and their mother Granny (Grace Zabriskie) go to get Bone’s birth certificate. The man at the desk is unwilling to hear their workarounds for stating Bone’s father’s name, and he stamps the paperwork with “Illegitimate.” Next, we see their aging home with its gray-wood siding, rusted metal roof, and yard strewn with firewood. Ruth and Granny are sitting on the porch, and Anney comes out to say a few angry words, being livid at the designation put on her child. The matriarch’s ideas about are: who cares what other people think?

In an attempt to alter the situation, Anney attempts to go to the courthouse one day, after she gets off from her job as a waitress, to “explain” the story to the clerk. It wasn’t that there is no father, her sister Ruth explains, but in the wild atmosphere that combined a car wreck and child’s birth, she had just gotten confused. The clerk is unamused and unconvinced, refusing to certify the birth certificate.

Soon after this, Anney is being courted by Lyle Parsons (Dermot Mulroney). He is a good and kind man who enjoys Anney and is a good stepfather to the young Bone. The couple quickly get married, and a child is on the way. But Lyle is killed in a car wreck. Anney is without a man again, this time with two children in tow.

Not yet twenty minutes into the movie, we see that Anney is plagued by two major problems: poverty and bad luck. Yet, her life is about to change. We believe things could be looking up. One evening, Earle brings his co-worker Glenn Waddell (Ron Eldard) into the cafe where Anney works, to introduce them. Then after Anney and Glenn have started dating, the courthouse – which holds Bone’s birth certificate – burns. It really looks for a moment like Anney, Bone, and her younger daughter Reese may be getting the breaks that they need. After all, Glenn is a Waddell, one of the well-to-do families in the area.

At first, it seems like Glenn will be a stand-up guy. He really likes Anney and spends time courting her in a nice way. But there are signs that he might have problems. We see him get into a fight with another man at the sawmill where they work, and the two beat each other bloody. Glenn also has trouble keeping a job. Perhaps more importantly to the story, we also sense that Bone has a bad feeling about him. Yet, by the half-hour mark, Anney is leaving her girls with Granny and the aunts to go marry Glenn. Granny has some choice words about the man, saying that the Waddells are stuck up, but Anney insists that Glenn loves her. What is perhaps most pertinent is: Anney is pregnant, again.

After the marriage, Glenn continues to seem like a good catch for Anney. They have moved into a nicer house, and we see him putting together a rocking horse for the new baby, which he hopes is a boy. The girls Bone and Reese play nearby on the porch. But things change very much on the night that Anney goes to the small hospital to have the baby. Glenn waits in the car outside, while the girls sleep in the back seat. Anney is having trouble giving birth, so it’s taking a while. While they wait, Glenn tells Bone to come up to the front seat, where he tells her that he loves her— but his tone is not what we would expect. His heavy breathing and strong embraces of the little girl in the dark show us our worst fears. Glenn molests his stepdaughter in the car, then shoves her aside and tells her to go to sleep. The tension of the scene is elevated when Glenn comes outside to the car in the morning, and he is distressed, revealing that their baby boy has died and that Anney can have no more children. Bone and Reese are left to cope with this on their own.

What follows is a series of moves for the family. An overdubbed narration from Bone explains that they moved constantly, because Glenn couldn’t keep a job. During these scenes, we see Glenn talking to his own father, a man in a suit standing outside a white-columned building. The elder Waddell says that, of his three sons, one is a successful lawyer, one is a successful dentist, and the last is Glenn. When will Glenn ever do something to make his father proud, the elder man wants to know. Then he answer his own question, Never.

As Bastard out of Carolina nears the one-hour mark, Anney has grown tired to Glenn’s inability to provide for their family coupled with his pride about taking help from their relatives. The girls are seen walking the railroad tracks, picking up bottles to get the deposit money to buy cans of pork and beans. During this scene, Reese asks Bone why Glenn doesn’t like her. At the house, Anney spreads ketchup on saltines for their dinner. When the evening comes, Anney takes her daughters to her sister’s house, while she goes out, and Glenn sits in the dark, since their electricity has been cut off.

By this time, Glenn has cracked. At his parent’s house for a child’s birthday party, his wife and stepdaughters are obviously unwelcome, and his father won’t pay attention to his news about a good job. The tension culminates in a physical altercation between the father and son when Bone drops a crystal pitcher of tea and shatters it. Back home, Glenn is working on the car when Bone and Reese run by, knocking over his thermos. He jumps up and scolds Bone, who mocks him to Reese as they run on. Glenn loses it and takes her upstairs where he beats her with a belt, while Anney pounds on the locked door, trying to intervene. Glenn is making so little money that Anney goes back to waitressing, which leaves Glenn home with the girls in the evening. This is when the beatings and the assaults begin for Bone with regularity. They are so severe that she steps gingerly, almost limping, while trying to hide her injuries from her mother. They can be denied no more when she is taken to the hospital and has a broken tailbone.

By this time, Glenn has cracked. At his parent’s house for a child’s birthday party, his wife and stepdaughters are obviously unwelcome, and his father won’t pay attention to his news about a good job. The tension culminates in a physical altercation between the father and son when Bone drops a crystal pitcher of tea and shatters it. Back home, Glenn is working on the car when Bone and Reese run by, knocking over his thermos. He jumps up and scolds Bone, who mocks him to Reese as they run on. Glenn loses it and takes her upstairs where he beats her with a belt, while Anney pounds on the locked door, trying to intervene. Glenn is making so little money that Anney goes back to waitressing, which leaves Glenn home with the girls in the evening. This is when the beatings and the assaults begin for Bone with regularity. They are so severe that she steps gingerly, almost limping, while trying to hide her injuries from her mother. They can be denied no more when she is taken to the hospital and has a broken tailbone.

After Bone has healed at her aunt Alma’s, she is taken to live with her aunt Ruth, who is sick. This relieves the tension with Glenn, and he passes out of our view of a bit. While she is living with her aunt, Bone is asked whether Glenn has ever touched her “down there,” and though she hesitates, she says no.

Then her aunt Dee Dee (Christina Ricci) shows up. Dee Dee is made up and wearing fine clothes in a way that none of the other women do. Dee Dee has come home because she is out of money, but she makes it clear that she never intends to come home again.

Soon, Bone is back home, and the same things start up again. Ruth has died, and when they are getting ready for the funeral, Bone back-talks Glenn, which leads to a severe beating. Anney lies on the floor helpless outside. Later, after the funeral when the family has gathered, Raylene discovers Bone’s wounds when she is helping the girl in the bathroom. She reveals the wounds to Earle and the other men, who take Glenn outside and beat him to a pulp. As the beating goes on, Anney protests, and Bone says her tearful apologies, believing that she has caused the situation.

With only about fifteen minutes left in the film, we know that the breaking point has been reached. Next we see Bone, she is living with Raylene, her independent-minded aunt who has remained unmarried. As she and Raylene talk, The Waddells ride by in their fancy boat and glare. Bone says that she hates them, but Raylene admonishes her not to build a life on hate.

As this is being said, Earle pulls up in his truck to take them to Alma’s house. Her husband has gotten antagonistic and violent, and she needs support now. While they’re there, Anney offers Bone the chance to come home, but Bone says no, she’s rather stay at Raylene’s. Anney knows that she has failed her daughter. During these scenes, we believe that the worst of it is over, but the worst is yet to come. When Bone is alone at Raylene’s, Glenn shows up. He is nice at first, asking for a glass of tea, but he soon reveals his reason for coming. Anney has agreed to come back to him but only if Bone agrees, too. We know that Anney knows about the beatings but not the molestation. What follows, after Bone says that she refuses to come back to live with him as though they’re a family, is a brutal attack and rape. Glenn loses it and attacks the girl with all of his might, eventually throwing her on the floor and assaulting her terribly. While this is occurring, Anney shows up and walks in on her estranged husband raping her child. Anney busts a milk bottle over his head and takes Bone to the car, as Glenn attempts to excuse his behavior and make it the way he wants it to be. For a moment, Anney shows that she does not know who to choose: Glenn, a violent rapist who does not provide for them, or Bone, the helpless victim of a grown man’s brutal assaults. At the hospital, a policeman tries to get Bone to tell him who did this to her, and we learn that her mother is not there at the hospital with her. Raylene takes her home.

In the end, Bone must come to terms with what her mother has allowed or enabled. Her aunt Raylene tries to explain that people seem to do terrible things to each other, even to the ones they claim to love. In the movie’s final scenes, Anney shows up to talk Bone, who by this point is stronger than her mother. They talk over a campfire at Raylene’s, a mother who has made awful mistakes and a child who has suffered for those mistakes.

Dorothy Allison’s 2024 New York Times obituary shares that her 1992 novel was published “to almost unanimous acclaim. Here was a novel that did not romanticize the noble poor, as Ms. Allison might say, or make cartoon characters of an eccentric Southern family, or lard its hardscrabble tale with ideology.” Continuing, we read, “Ms. Allison was lauded — along with other contemporary Southern writers, including Harry Crews and Bobbie Ann Mason — as pioneering a new genre, often called Grit Lit or Rough South.” Another of her novels, 1998’s Cavedweller, was also made into a movie in 2004.

As a document of the South, Bastard out of Carolina deals with some brutal realities. The kinds of laws that declared Bone to be “illegitimate” and the kind of behavior exhibited by Glenn are not particular to the South, of course. But the practical realities that led to situations like these were common in the South: patriarchy, white supremacy, and poverty. Looking at Bone’s case, a child without a father could not be considered “legitimate.” (Every child has a mother, indisputably, but the mother didn’t conceive a child without a partner, which makes these laws and norms quizzical at best. The mother and the child live with the consequences of the father’s absence.) In the movie, this is also a world of white people, even though South Carolina has long had a significant black population. The only African Americans that we see are a small group gathered by a fence during one of the scenes when the family is moving into another house. This detail tells anyone who understands Southern culture that Glenn, Anney and the girls have been “reduced” (socially) to moving into a black neighborhood. So it has be clear right away that the story we’re watching is not so much a story of the South as it is a story of the poor, white, patriarchal South. Anney’s problems and subsequently Bone’s problems arise from those realities.

Considering this further, we also have to add ignorance and classism to this mixture. Almost all of the characters who we meet in Bastard out of Carolina are either rough, rural people who eek out a living from meager resources or members of a disposable Southern working class. Glenn comes from the upper echelons of this local society, but his first flaw – but by far not his worst flaw – seems to be an inability (or an unwillingness) to capitalize on the advantages of his birth. His father remarks that both of his brothers carried their privilege forward, but Glenn is a disappointment because he has not. Further, Glenn cannot hold a job or maintain a home despite pleading with Anney to marry him and trust in him as a breadwinner and head of household. This film may be the story of Bone, or potentially of Anney, but its antagonist Glenn plays the pivotal role in what occurs. The lives of these women and girls would be hard without Glenn . . . but their lives are absolutely terrible with him. Neither Anney nor Bone did anything to bring these events about; it is Glenn’s decisions that affect things the most, and the worst. Glenn’s awful crimes emanate from his character flaws and from his low/fallen status in a class-based culture. In this society, Glenn has no power, so he finds his power in physically and sexually abusing Bone, a helpless young girl whose mother has a desperate need for a husband. He is an ignorant, unskilled outcast, whose well-to-do upbringing has not prepared him for the realities of a working-class life. And he fails to be Man in every way. (Though he may not be a stellar example, Earle is the best example of manhood in the story, since Glenn’s father is a loveless and only concerned about jobs and status.) Sadly, by the end of the film, we’re not looking for the female characters to triumph so much as survive. Of all of them, Raylene seems to fare the best. Why? Perhaps because she remains unmarried, lives humbly and simply, and relies only on herself.