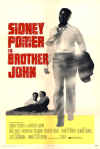

Southern Movie 81: “Brother John” (1971)

The Southern Movies series explores images of the South in modern films as well as how those images affect American perspectives on the region.

The vaguely surreal 1971 drama Brother John features a juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated events in an Alabama small town, and the mystery of the situation is heightened by the return of a local man who “disappeared” years earlier. The film’s story revolves around a town where there are both racial struggles and labor struggles happening. The title character, John Kane (Sidney Poitier), arrives as the tension is reaching a fever pitch; it is explained early in the film by the town doctor that John’s sudden arrivals point to a prescience that the man must have. Of course, some locals connect this arrival to rumors of an outside agitator, possibly or probably involved in a plan to make tensions worse. Directed by James Goldstone, the film was written by Ernest Kinoy, who later wrote the 1972 western Buck and the Preacher and the 1976 biopic Leadbelly. Brother John incorporates the real tensions in the early 1970s Deep South into a tale that toes the line of magical realism but never quite crosses it.

The film begin with credits rolling to soft music as we watch an old white man in a convertible drive through a small Southern town. His car is beat up, and he is anachronistic and quirky, which we see as he drives the wrong way through downtown and almost causes a crash. But when he arrives at his office, we find out that he is the town doctor Henry Thomas (Will Geer).

Inside his office, Dr. Thomas is examining a middle-aged black woman named Sarah, something that viewers in the early 1970s would recognize as odd, given the racial climate of the day. However, there is a calm rapport between doctor and patient. After she gets dressed, they talk as he examines her file, remarking that he hasn’t seen her in a long time. He also remarks that she has been in some degree of pain and wants to send her over to the hospital for some tests. The woman’s stoic resolve tells us that something is wrong, and she knows it. During their conversation, he asks about her brother John, and she tells him that, other than a Christmas card last year, Sarah hasn’t seen him in seven years.

In the next scene, we are made to understand what our story will entail. A white man in a suit pulls up to Dr. Thomas’s office in an expensive new car. He strides in, after noticing where his father’s car has yet another bit of damage, and finds a black preacher inside with the doctor. This is his son Lloyd (Bradford Dillman), who has come to speak with his father, though the doctor had actually left a message about seeing his son anyway. Fortuitous. Inside the living room of the doctor’s home-office, the father explains to his annoyed son about John Kane. The boy had been born during a bad storm when the lights went out, and as he grew up in the town, led a mostly normal life. The doctor had treated him for the kind of ailments a boy might have, like a cold or a hurt leg. Then at sixteen, John just disappeared, left town. John later returned on the day that his mother had a stroke and died, though no one had notified him about it. There was no way that John Kane could have known that his mother would fall ill and die. Then he left town after the funeral. It might have been a strange accidental circumstance, but he also showed up on the day his father died in Indiana. John Kane’s father was working far from their Alabama home when he fell off the building where he was laying bricks and died of his injuries. When his sister Sarah – the woman we just saw being examined – sought the necessary paperwork to collect the life insurance, John Kane had already been there, had been at their father’s deathbed, and had the paperwork completed. Lloyd seems uninterested in this strange story, but Dr. Thomas insists that John will certainly arrive in their small town, since his sister has malignant cancer and will die very soon. Lloyd, a busy man, doesn’t care. There’s a labor strike going on, and he has to go— there are meetings to be had.

When Lloyd arrives at the industrial facility where the strike is happening, there is a crowd of two or three dozen men shouting, carrying signs, and harrying drivers as they enter the guarded gate. As men in suits and sheriff’s deputies stride around, it is easy to detect that everyone in power (inside the gate) is white, while everyone disputing that power (outside the gate) is black. After pulling in and parking, Lloyd is immediately accosted by two white in men in suits, who gripe and complain then make allusions to getting him elected, though Lloyd reminds them that they didn’t get him elected. (We understand that they are the out-of-towners who own the operation.) Soon, the sheriff arrives, and Lloyd has to shake the capitalists off to handle local business the local way. The suits have gotten a court order that the strikers can only have a dozen men at the gate, and the black men clearly have more than that. As the sheriff walks away to handle it, the capitalists tell Lloyd that they’ve heard from their pals in New York that the laborers have a union man coming to help them. Outside the gate, the white sheriff addresses a black man name Charlie Gray about the number of protestors, reminding him that it’d be shame to have to crack heads. Charlie Gray understands the sheriff’s logic in having most of the men watching from across the street, while twelve men stay in place. Their interaction is faux-cordial and full of insinuations, but it gets the job done.

The scene then shifts to a hospital where Dr. Thomas is walking with a nurse. She is explaining to him that Sarah has died and that her family is there. The hospital’s doctor didn’t want to “take responsibility” but preferred to let Dr. Thomas do it. He finds Sarah’s family, and they are quietly grieving. He asks if they’ll need to contact other kin, like her brother John, but they just shake their heads. Leaving them, the doctor goes around the corner to Sarah’s hospital room, and there he finds her with a sheet covering her corpse— and John is standing there. In a black suit, his back to the door, John makes no sound. Dr. Thomas puts his hand to his face in a gesture of shock, then addresses John, who turns around and greets him quietly and without emotion. The two have a brief conversation, where the doctor tries to illicit information from John, but his grave stare and his short answers let both him and us know that that won’t happen. John claims that he was “passing through,” and when asked how long he’ll be staying, he says, “Not long.”

At the funeral, Dr. Thomas is the only white man among the small crowd, and John stands expressionless over by himself. The sheriff is at the top of the hill, watching, and when it is done, he speaks to Dr. Thomas, wanting to know who John is. He intimates that John may be connected to the labor struggle, and the doctor objects vehemently, saying that John was born and raised in their town. He’s no outsider. Here, we also see more of what the beginning of the film showed us, that Dr. Thomas’s erratic behavior coupled with his kindheartedness means that people only take him half-seriously.

Afterward, tensions are rising. John and Dr. Thomas have a tense moment at the gathering, where the elder man offers a handshake that is just barely accepted, while across town, the sheriff is on the phone warning Lloyd that John is the union man they’ve been expecting. Once our focus is back on the evening funeral gathering, John is re-introduced to Louisa, a local woman who he remembers from childhood. She has gone outside to escape a man named Henry Burkhardt (Paul Winfield) who is interested in her. John provides a little cover for her escape, then tries to continue the conversation with her. The two catch up for a moment, flirt a little, and trade stories. Louisa went away to New York and was a teacher, before returning to their hometown to teach there. She asks what he has been doing, and all he will say is a cryptic: “Working . . . but that’s done now.” He says that he will stay a few days then leave again. For a moment or two during this conversation, we see some humanity in John, a few smiles and chuckles, then he returns to the possibly angry, maybe bitter, defiantly stern resolve that we’ve seen in him so far.

While John is reminiscing with Louisa, Lloyd and the sheriff are searching his little motel room. They find almost nothing but his suitcase. In it are a couple of confusing glimpses into the man they’re suspicious of: a cluster of clippings from newspapers all over Europe, a couple of religious books from various faiths, and a handful of journal notebooks with no writing in them. They also find his passport, which is stamped from places all over the world. But John arrives, and then they jog out of there and retreat in their cars. He sees them leaving.

After they depart, Lloyd really digs in to find out who John Kane is. Their first stop is the doctor, who only provides the few vague facts that he had already shared. But Lloyd is determined, and the way that he rattles off city names from John’s passport, it seems like he is thinking that John is involved somehow in international politics or in the spy game. The next day, Lloyd takes it to man who is a government connection. He has asked for what the feds know about John Kane, and they meet in cafe— but no one has ever heard of John Kane nor knows anything about him. So what was he doing in places like Peking, Havana, and Cairo? And how did get there? And how did he pay for it? Neither of these white men has any idea. John Kane is not working with the CIA, and the feds have no knowledge of him being involved in any radical groups.

Next we see John, he is entertaining Louisa’s class outside of the schoolhouse. He is acting silly and saying strange words, while the children – some white, most black – giggle and play along. When he is done, Louisa asks where he learned this African folktale, and he says that he was there for a telling of it. Then, as they wander briefly, he catches sight of the outbuilding bathroom where he carved his name as a boy. There is a brief scene then where he ponders the carving while a little boy who is trying to pee at a urinal watches him awkwardly. We get that he has ambivalence about his past there.

After that, John and Louisa go walking together. She asks about his plans, and he remains vague and secretive. So she replies at length about how their little community is watching them, how he will leave her to face the rumors and speculation. Eventually they end up outside of town, where John looks over the industries from the hillsides. They appear to be quarries of some sort. This group of scenes, which commingle their budding love affair with surveying the town’s realities, closes with gunshots, as a white man in a cowboy hat repeatedly blasts a rat’s dead body with a deer rifle.

The focus then shifts back to Lloyd and the sheriff. They’re in the offices, talking about John, and the sheriff reveals that he found some history on John, who got a couple of months on a road gang in Texas for a vagrancy charge but walked off. There is a warrant out on him, still, and the sheriff wants to use it to arrest the man he believes to be a union organizer. As they walk, they go into Lloyd’s office – the door says County Solicitor, so we now understood what his elected role is – and the two men talk. Lloyd wants to bust John on something big, which takes time, but the sheriff wants to go ahead and get him off the streets, before that night’s strike meeting.

That evening, John is sitting at the dinner table with his brother-in-law Frank. They discuss Sarah’s life insurance, and Frank tells John how Sarah had always made people believe that he made more money when she actually did. It was a point of pride for her that a black man be regarded as a Man. While he is saying this, we see two sheriff’s deputies walking up the front walk. John sees them from where he is sitting, but Frank doesn’t. The two teenage children are in the kitchen, washing dishes, and don’t see the lawmen either. When they knock on the door, the teenage son lets them in, and the elder deputy of the two has clearly come to harass Frank and John. He first begins to harry Frank, who tries to stand up for himself but is cowered. John, on the other hand, is calm and watchful, remaining silent while this happens. Ultimately, he asks the antagonistic deputy if they came to “talk” to him, and the deputy replies with a sly smile that they did. So John invites the man downstairs into the basement. The deputy believes that he is going down there to rough up a black man who will cow down like Frank did, but instead John outdoes him and kicks his ass handily, hitting him with repeated body blows – something that looks like jujitsu – leaving no marks on his face. Meanwhile, the teenage son has gone outside and watches this beating from a window. After seeing that he has defeated this aggressor, John helps the deputy up, puts his hat and gunboat back on him, and leads him back up the stairs without a word. He has made his point, and the two deputies leave in silence. The teenage son who witnesses it comes inside again and makes a small gesture to console his father, who was just humiliated in his own home.

This scene, which comes at the halfway point in the film, is important to both film history and to Southern culture. In Frank and John, we see two kinds of African American men in the South: one who has built a life and has a family and a future to consider, and one who uprooted himself and will not have to face long-term consequences in the community. The cruel deputy cows Frank without ever laying a hand on him, by naming his employer, by alluding to Jim Crow social norms, and by intimating that he will have a hard time ever living a normal life again if he is defiant. The violence against Frank is psychological, not physical, and relies on potential consequences. John is a different matter. The deputy then believes that he will be able to assault a black man who will be compliant for the same reasons that Frank was, but he is wrong. Very wrong. John is not affected at all by the psychology of it, and he is a superior fighter to boot. And he even beats the deputy within his own rules, using the silence, the lack of witnesses, and intimidation to subdue a man. In short, John treats the deputy like the deputy would treat a black man. (Consider, too, in light of the slap scene in Poitier’s 1967 film In the Heat of the Night, this full-on ass-kicking of a white power figure takes that motif all the way.) So, everything is in place for the second half of the movie.

This scene, which comes at the halfway point in the film, is important to both film history and to Southern culture. In Frank and John, we see two kinds of African American men in the South: one who has built a life and has a family and a future to consider, and one who uprooted himself and will not have to face long-term consequences in the community. The cruel deputy cows Frank without ever laying a hand on him, by naming his employer, by alluding to Jim Crow social norms, and by intimating that he will have a hard time ever living a normal life again if he is defiant. The violence against Frank is psychological, not physical, and relies on potential consequences. John is a different matter. The deputy then believes that he will be able to assault a black man who will be compliant for the same reasons that Frank was, but he is wrong. Very wrong. John is not affected at all by the psychology of it, and he is a superior fighter to boot. And he even beats the deputy within his own rules, using the silence, the lack of witnesses, and intimidation to subdue a man. In short, John treats the deputy like the deputy would treat a black man. (Consider, too, in light of the slap scene in Poitier’s 1967 film In the Heat of the Night, this full-on ass-kicking of a white power figure takes that motif all the way.) So, everything is in place for the second half of the movie.

Proceeding from that tense scene, we move to the union meeting. There is a crowd of rowdy white people outside the downtown building, and we can see shadows of the black men upstairs. The sheriff is there, maintaining order, and when the younger deputy arrives, the sheriff asks where his partner is. He went home, he didn’t feel well, the young deputy says. Soon, the meeting lets out, and the black workers emerge. Charlie Gray is among them, and he runs into John and Louisa. Charlie and John are old friends, it seems, and the trio head to the bar to get beers and talk. Charlie tries to convince John to join them, saying that he has avoided his responsibility long enough, a remark that John doesn’t appreciate. The tone changes, too, when Henry Burkhardt tries to grab Louisa on her way to the bathroom, and John’s attention shifts from Charlie to Henry. We find out here why Henry is fixated on Louisa; they had a sexual relationship as teenagers, and Henry wants to get that going again. Louisa does not. After that, John and Louisa leave together, happily, and end up in her little house. John is visibly dismayed at the poverty of her situation, but they soon kiss on the bed.

Among the people who won’t give up on finding out the truth of John Kane, Dr. Thomas is still at it, too. He and the black preacher go to see Miss Nettie Wheelock, an elderly black woman who was the schoolteacher when John was a boy. They talk outside, where she sits in a rocking chair and eats plums. She takes some urging but she remembers him. Long ago, John had been offered a scholarship to a nearby school in Marion – there have been several references to this real west Alabama town already, which places our story in the Black Belt – but John turned it down. He said that he didn’t have time, that he was leaving. Miss Nettie couldn’t believe it, that he would turn down a good opportunity to go and learn then come back and serve his community. She also told them that she asked him when he was coming back, and his response: when the wind blows in. Though she doesn’t understand the strange response, Dr. Thomas does. The last thing she tells them is equally important. She gave him a journal before he left and told him to write something in it every day. We have seen this journal when Lloyd and the sheriff searched John’s room. He still has it, though it is blank.

Now, at the two-thirds mark with one hour down and thirty minutes to go, we sense that something must happen with John Kane. Everyone wants to know about him. Louisa wants him to stay and be with her. Lloyd and the sheriff have their eye on him, and they have a warrant to use against him. Charlie Gray wants him to join the strike. All of his blood relatives are dead, and only Frank and the two teens remains of his family. He has attacked a lawman and beaten him down, and we know that won’t just go away. And all the while, John insists that he is leaving in a few days. We have to wonder, why in a few days? why not go ahead and leave, if he’s going to? Whatever will happen, it is going to happen soon.

Driving together in the evening, John and Louisa are talking about hellfire and damnation. Louisa asks if he believes in such things, and he replies that he has seen hellfire already. About damnation, he is more general, saying that we may not have to answer for our individual sins. John proposes that the human race may have to answer for its sins, collectively. This seems to bother Louisa. (It would also point to the interpretation that John has been involved with the communist party.) Just then, a car comes driving up behind and rams them. John is driving Louisa’s little VW Bug, which has a rear engine, so it’s something to worry about. We assume at first that it is racist whites, but it is actually Henry and two of his friends. John tries to escape but Henry’s muscle car is too much for him. He comes to a stop, where the three jump out and begin to goad him out of the car. John gets out after a moment, and Henry wants to take him on one-on-one. He faces the same outcome that the deputy did. Then the other two try, and John does them the same way. Adding to the tension, a sheriff’s car drives up, and who is it but the deputy that John beat down earlier. We are thinking at first that this will not bode well for John, but the deputy just tells John to drive away. Henry tries to yell into the car to Louisa that he loves her, but it’s too late for that. After John drives off, the deputy tells Henry and his two friends that, well, sometimes it just be like that.

Back at Louisa’s house, she invites him but he declines. They then have the talk. John tells her that he is leaving tomorrow. In the conversation that follows, which defines in vague terms the circumstances of being Brother John and knowing Brother John, he explains that he must leave, alone. As much as he might want a normal life, like the ones his parents had, it just isn’t possible. Louisa accepts this sadly, but with mild protests, trying to find ways that they could be together.

Our attention is then turned to Dr. Thomas, who is driving alone at night. As he rambles through mild traffic, running red lights and swerving, he is thinking of what Miss Nettie said, that John told her he will leave when the wind blows again. Then he crashes! Back at the station house, Lloyd is handling the situation, telling the deputy that Dr. Thomas will surrender his drivers license. In the other room, the sheriff and another deputy are using ultraviolet light to try to find writing in John’s journals, which the sheriff got a search warrant to seize. They can’t find any writing in any of them, to which Dr. Thomas begins to chuckle. The old man tells these lawmen that they won’t find anything – remembering Miss Nettie’s instructions to John to write down anything he found interesting each day – and he says the fate of the world depends on what John writes in those books. His half-grinning monologue implies that John is an angel or at least some form of messenger for God. So now, it’s on. The conversation turns to the fact that John plans to leave tomorrow, he has said so and everyone knows it. Lloyd gets panicky and tells the sheriff to arrest him. The sheriff argues back, reminding him that Lloyd wanted him not to be arrested so he would leave on his own, and now that he’s going to leave on his own, Lloyd wants him arrested! Lloyd sneers at this and says to go arrest him, now.

In the light of day, the sheriff and his men are surrounding Louisa’s little house. The sheriff wants to know where he is, and Louisa says sadly that she doesn’t know. Then they find him, just sitting calmly on the little porch outside his motel room. They scurry around, taking up positions, and he never moves. Next we see, Lloyd is confronting John in the jail. John remains expressionless and answers every question. Lloyd wants to know why he had been to all those countries. To see the world, John replies. How did pay for it? By working, says John. How did he get into those forbidden countries, like China and Cuba? Nobody stopped me, John says. What languages does he speak? John lists several. Why are the journals blank? Because I haven’t written in them, John replies. Then why would he keep them, Lloyd wants to know. To remember, John tells him. Lloyd is frustrated because he wants for there to be something sinister about it, but watching it, we see that John may simply be a man who has no regard for political or social norms. He may simply be a man who does as he pleases and who isn’t harming anyone in doing it.

Then Lloyd is called away from the cell to handle an issue with the strike at the industrial facility. (The sheriff reminds Lloyd that he has plenty of experience “interrogating negroes” and could try some different methods, but Lloyd says no, he doesn’t want any lawyers coming in with reasons to take issue.) Out in the lobby, the black preacher and Louisa want answers about why John was arrested. Lloyd tells them about the warrant but refuses to share more. (Keep in mind, this is a man who was just frustrated by someone refusing to give him answers.) While they’re talking, the sheriff bursts in, telling everyone to get to the industrial facility. He divulges that Charlie Gray has been killed with a shotgun, and the shit is probably about to hit the fan. He asks the black preacher for his help in calming the black community and ensures him that the law will handle the killer, no matter his color. Nearby, Dr. Thomas is eavesdropping and watching the whole thing. As he does, Louisa mentions tearfully that John knew that Charlie was dead . . . before it had even happened. Dr. Thomas perks up at this and looks out the window. The wind is blowing!

The last ten or twelve minutes of the film are devoted to a conversation between Dr. Thomas and John Kane. The doctor asks the same kinds of questions that Lloyd asked, but he does so with more compassion and with an open heart. John tells him that he has seen suffering, much of it, and describes Man’s inhumanity to Man. Dr. Thomas isn’t satisfied, wanting John to confess that he is part of a Grand Plan, that he is a supernatural being. John gives him no such satisfaction. Then Dr. Thomas says something that may well be the culmination of it all, with a remark about John “being born black in a town like this.” He also uses “we” a few times, implying that he and John are made of the same materials. But the old man wants to know: is there hope? what about love? “That may not be enough,” John tells him.

As the unkempt little jailer begins to close the windows against the rising wind, John stands up and puts on his jacket, as though he were leaving. Dr. Thomas calls for the jailer to come open the door and let him out, after he has given John the journals that he snuck out of Lloyd’s office. He still wants some consolation, some hint about Armageddon or the future. Finally, he asks John if they will ever see each other again. No, they won’t. As the two men stand face to face, the jail door flings open behind John though we never see the jailer there. It may have been opened by the jailer . . . or maybe by John’s powers? The scene then switches to the wind whipping flags and tree branches and Dr. Thomas’s sign. That’s all we get.

It is clear that John Kane is a symbol, albeit a strange one, and one whose interpretation requires some knowledge of Southern culture. He is a black man from the Black Belt of Alabama, raised in a small town by hardworking people who are stymied by poverty and Jim Crow, and he is the one who threw off those shackles and became a self-made man. As such, he is mysterious and problematic. Why did he leave? No one understands. Where did he go, and why? He will not explain, knowing that it would be pointless. Thus, as an enigmatic figure who will not be controlled by conventional means – unjust law enforcement, Jim Crow, poverty – he becomes every kind of boogeyman that white people can conjure and every kind of hero that black people can imagine. To whites, he could be the Angel of Death, he could be an agitator, he could be a communist. To black people, he could be a hometown boy made good, he could be the one who escaped, he could be a leader or a savior. John Kane is at once desirable and frightening. People want to know about him but are terrified of what he might be. Put bluntly, he is an anomaly— a black man from the South who has refused to abide by Southern racist norms. And as such, he is always being pulled by a community that he cannot live in by people who simultaneously want what he has but who don’t want to do what it takes to have it.

To the average viewer, Brother John might be psychological thriller or a suspenseful drama, but as a document of the South, it contains subtle nuances that make it an exacting narrative. First among these features is the fact that John disappears as a sixteen-year-old, and among the white community, only Dr. Thomas notices. This aspect of the story gives a glimpse into black life in the pre-Civil Rights Deep South. Black people could “disappear,” and white people saw it that way because they didn’t actually care what happened to a black person and because black people told white people as little as possible about their personal business. As a man who regularly and comfortably crosses racial boundaries, Dr. Thomas is different. He saw John as a person and recognized his sudden absence. The second interesting feature is the outside ownership of the industrial facility where the strike is happening. From the Great Depression on, community leaders like Lloyd were recruiting Northern interests to bring industrial jobs to low-income areas in the rural South. This exploitative arrangement was accomplished with promises of cheap, disposable labor, while unrest among the workers was typically handled by the sheriff and local leaders, who were often profiting themselves. Local leaders’ insistence on maintaining a strong influence over the workers was meant to show Northern industrialists that the situation could be kept under control. It was – and still is – a complex mixture of local politics and economic development, one that illustrates how the wealthy are more interested in uninterrupted profits than in workers. Third, we have the scene in Frank’s home with the deputy. This dualistic paradigm is put out there for anyone to see: the hometown black man versus the rootless black man. A black man who wanted to lead a decent, hardworking existence and raise a family must sacrifice his dignity and play the long game. Certainly, Frank’s labor at the sawmill is physically demanding, but his wife, who cleaned houses for a rich family a few days a week, made more money. The deputy even makes reference to Frank being easily replaceable. Seeing Frank’s circumstance helps us to understand why John “disappeared” and why he usually has these enigmatic looks on his face.

However, some problems do exist with the Southern-ness of this film. First, in the fictional town of Hackley in fictional Calawah County, there is a very nice and very modern downtown area. A little too nice and a little too modern. Several characters make references to Marion, a real city that may have been known to some in 1971 as the place where Jimmy Lee Jackson was killed, an event that incited the Selma to Montgomery March. Yet, Marion is the seat of Perry County, and itself only a tiny town with only a small square at the center. If the town of Hackley had existed, and if a county solicitor’s office was there, it would have had to be a county seat— meaning that going to Marion for something would not be necessary. The dialogue seems to imply that Hackley is a tiny town that relies on Marion, but its local amenities are too upscale for that to be true. Also, with regard to the union business, some of the black dudes are little too hip and not country enough. Charlie Gray is way too hip. Though the film is set in the Black Belt of Alabama, there are some things are not quite Black Belt about it.

Other things to consider about this movie revolve around the fact that, while John is at the center of the plot, he is not a dynamic main character. John is the same person when he arrives and when he leaves; he doesn’t change. The question becomes: is this a story about Dr. Thomas or about Louisa? Both are hopeful figures in the post-Civil Rights paradigm. Dr. Thomas is a white liberal, whose character is similar to Richard Burton’s in 1974’s The Klansman, and Louisa is an educated black woman, who went North then returned home to raise up the next generation. Given the amount of screen time, it would be more feasible to say that this is a movie about Dr. Thomas, since we see him in the first scenes and the last. But if that were true, then Brother John cannot be, as one blogger called it, “the blackest movie ever made,” because it would then be about the redemptive quality of the black experience in lifting up white consciousness. If that’s the theme, then Lloyd is the villain, as he stands in the way of both John and his father. That interpretation would mean that Brother John is mainly about how affluent white efforts at economic development in the 1970s just ruin everyone’s lives. The sheriff can’t maintain order, the workers aren’t treated right, Charlie Gray is murdered, all bad. (Keep in mind, once again, that small-town economic development efforts and a Northern industrialist were also at the center of the conflict in In the Heat of the Night.) One criticism of race-focused movies like this one – seen mostly prominently in To Kill A Mockingbird – is that even stories about black triumph end up being about white liberation. Maybe that’s true here. Maybe not.